Exercise Tiger Debacle: 27/28 April 1944

The Allied Invasion of northern France was finally set for the late spring of 1944, after remorseless pressure from Stalin had finally overcome Allied reluctance to launch an invasion so soon.

Montgomery was responsible for much of the planning. Somewhat belatedly, Montgomery added a requirement for a second U.S. division which would land on ‘Utah’ Beach, in addition to the one already planned for Omaha Beach. As a result, “Assault Force U” was hastily formed to handle the transport and landing on Utah.

The planned Allied landings were covered by an outstandingly successful deception to conceal the exact place and time, but it was no secret to the Germans that Allied forces were conducting large-scale rehearsals on British beaches in preparation for an invasion. These preparations had begun in earnest as early as January 1944 but because of its late formation, Assault Force U was behind the game. By late April It was only just ready to start large-scale exercises. The location selected was Slapton Sands, due to its close resemblance to Utah Beach.

Exercise Tiger was a full-dress rehearsal and was scheduled for 22 to 30 April 1944. Under the command of US Rear Admiral Moon, Force U would conduct an extended sea journey to simulate precisely—sea sickness and all—the Channel crossing. The ships were fully loaded, as were the vehicles on the ships, with fuel and ammunition (far more than was strictly required), but again, the intention was to hew as closely as possible to real operation.

Almost the entire Force U participated, including 21 tank landing ships (LST), 28 large utility landing craft (LCU[L]) 65 tank landing craft (LCT) and nearly 100 smaller vessels. Although it was mostly an American force, British ships also took part. The mixed nature of the force was viewed with great worry by senior U.S. Navy leaders, who assumed that mixing U.S. ships with ships of other navies would lead to communications problems and other foul-ups – and they were absolutely right.

The first-echelon landings on 27 April were marked by significant confusion. Allied ships bombarding Slapton Sands beach with live ammunition to make the exercise as realistic as possible. Delays and communications problems led to Rear Admiral Moon ordering an hour’s delay only five minutes before execution, but not surprisingly many units did not get the word and some troops were landed into the live fire, resulting in an estimated 450 deaths.

Then things got worse.

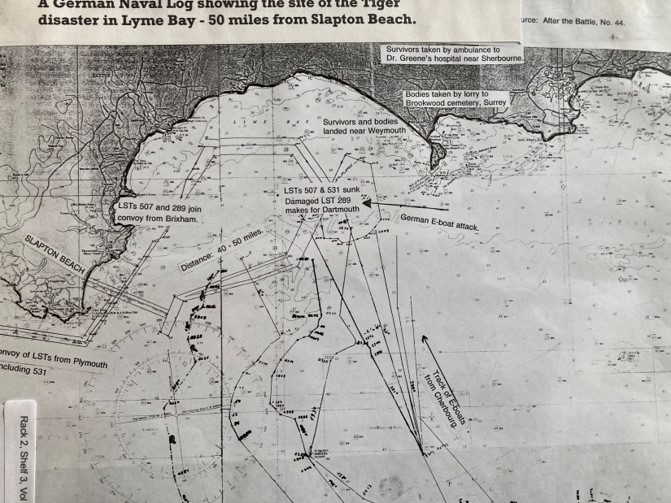

Elements of the second-echelon force departed Plymouth, Brixham and Portsmouth for a night transit to the landings at Slapton scheduled for the morning of 28 April. The British destroyer HMS Scimitar was to act as escort, but Scimitar and another vessel collided and – unknown to Moon because of radio silence – had had to return to port. Worse, by monitoring the wrong frequency, the U.S. convoy did not receive broadcast warnings when British radar detected a force of nine German Schnell-boats (fast torpedo boats) approaching.

At 0207 a German torpedo struck LST-507 amidships. The hit was devastating, starting a massive conflagration in the main cargo area as vehicles full of petrol ignited, creating a blast furnace effect within the ship. Many died in the flames. Eleven minutes later, two torpedoes in quick succession hit LST-531 and perhaps more mercifully sent her to the bottom in only six minutes.

The skipper of LST-289, saw torpedoes inbound in enough time to put the helm hard over and avoid a broadside hit. One torpedo hit the stern which broke off and sank. By this time, however, chaos had gripped the force. LSTs were firing on each other in the dark and at least one was hit. The soldiers were only support troops who never expected to be in front-line combat. They did not have Navy kapok life jackets, but had been issued an inner-tube device, for which they had not been adequately trained, that when worn incorrectly would flip the soldier over and drown him. Many soldiers perished in exactly that manner, or they died of hypothermia.

Exactly how many U.S. Soldiers and Sailors were lost that night remains contentious, even today. One source says that the 749 figure generally used only counts Army and that adding the Navy’s death toll increases the total to 947. Other sources assert that all these numbers were grossly undercounted in the massive cover-up that followed.

It is quite possible that perfectionist Moon did not cope well with the numerous foul-ups during the rehearsal. The loss of so many men under his command troubled him greatly. Talk about the possibility of him being held to account by a court-martial, as some senior Navy officers seemed to desire, probably didn’t help his state of mind. All may have been factors when Moon tragically took his own life on 5 August 1944.

Importantly however, numerous lessons were learned from the debacle – all of which Moon rapidly implemented before the D-Day landings. Force U’s performance during the actual invasion was exemplary, and Moon handled the force adroitly. German resistance at Utah Beach was stiff, and Moon deserves much credit for overcoming it.

Dartmouth Museum is supporting the Flavel and Helen Deakin with images for the ‘Exercise Tiger 80th Anniversary’ events on 27th and 28th April 2024

If you are interested, the Museum has an extensive collection of relevant images and documents for inspection. Enquire at Reception. There are also DVDs and a fully researched book by Gail Ham on sale in the Museum Shop.